| | |

| HITCHCOCKfS PSYCHOANALYSIS |  |

| |

| MIKIRO KATO

ASSOCIATE PRORESSOR OF CINEMA STUDIES

UNIVERSITY OF KYOTO

| |

| | |

| P@The Ideal Spectator

The analysis of a filmfs texture begins with the assumption that an eidealf spectator watches a film; a spectator who can read multiple meanings into a single cinematic narrative and grasp how each of these meanings interact and interweave into a rich texture of interpretations. Such an ideal spectator, even when watching a film for the very first time, is acutely aware of all the different shots and scenes, which are otherwise a single-narrative cinematic projection. This generates the conscious awareness of their relevance to each other within the whole composition of the film. Not only is such an ideal spectator able to consider these multiple film interpretations of different scenes and shots in a wider complex of the whole film, but also at the same, they are completely sincere in the self-projection of individual feelings that a viewing of a film generates. Therefore, it is reasonable and very possible to make a thorough textual analysis of a film, assuming the existence of an ideal spectator.

With this initial proposition of the existence of an ideal spectator, it can also be inferred by means of assumption that an ideal spectator can also make a significant guide for a film studies student. Since the history of film studies is still rather short, such a student is given relative interpretative freedom in the use of their intellectual faculties. Therefore, first of all, a film studies student is to set their sights on becoming an ideal spectator, and through this self-educational process they are to acquiesce themselves with the economic, cultural, and historical factors concerning film production in order to be able to eventually enjoy exploring the mechanism of the film and its textual interpretation in a more refined and imaginative way.

The reason for alluding to the process of education and exploration, although it may distract the reader from the main objective of this essay, is to stress and underline the two major sources of cinematic stimulus that arouses the intellectual interest in watching films. And these interests are intrinsically defined as well as motivated by two kinds of film analysts: the film critics and the film scholars. Film critics induce us to go and see new and interesting films. Film scholars inspire and encourage us to have another look at those films that we have already seen in order that we may be able to come to not only appreciate the textual richness but also the potent meanings that we may not have been able to grasp at the first viewing, and therefore enjoy the cinematic text in more depth and with much more refined intellectual and emotional richness. Film critics urge us to movie theater; film scholars to self-project introspection. Film scholars guide us not only to be satisfied with a single viewing of film but also to acquire an understanding of the process of glookingh. And it is the process of looking which is the most important aspect to develop a filmic perspective glookingh at films from a multiple viewing and analytically interpretative perspective that can be made the starting point for the argument on the overall process of self-education, cinema exploration and film criticism.

Films were originally considered as transient products. Although detailed knowledge of filmmaking, several different technical skills, and a considerable amount of investment were required in motion picture production, each film was shown in the movie theater for no more than two weeks and was quickly removed and replaced by another brand-new film. In the film business, a degree of freshness was the top priority. In other words, films were treated as a sort of weekly magazine. The majority of spectators/readers were likely to forget the narrative and cinematic particularities of individual films soon after their release. Films are mass-produced and therefore implicitly reflect the spectatorfs common desires and different individual dreams. Therefore, the ideal spectators are those groups of people who are eager to watch films straight after they are released. Consequently, these committed cinemagoers must have relished each occasion of viewing a new film and must have savored it with a real cinematic taste. They were entirely different from later spectators who enjoy these films on video or DVD, not in the movie theater but in the comfort of onefs home.

This essay, therefore, makes a thorough film analysis by means of assuming not only what the ideal spectators of the time thought about the film, but also how they could have reacted to the cinematic projection, its filmic narrative and texture. Namely, how they received and enjoyed a film when it was screened for the very first time. Of course, it must be acknowledged the spectatorfs feelings and their cinematic judgments that one may assume in the ideal spectators have, are rather hypothetical, and therefore they might not always coincide with our own. Nevertheless, it is my belief that this kind of experimental analysis should become a significant step for our future film studies.

| |

| | |

| Q@Linearity

Films have distinctive traits comparable to other narrative media such as novels and comics. However, they have all in common the aspect of linearity. In a film, the editing matches temporal relations from shot to shot, from scene to scene; it is a crucial structure for maintaining a succinct narrative form. A filmic narrative cannot be established without some kind of linearity through which a series of charactersf motions and emotions, with causes and effects interrelated framework, are conceptually structured and cinematically elaborated. The spectators have no choice but to follow the linear progression of the filmic narrative through the compilation of cinematic images. They cannot skip over some parts or go back to already viewed shots, unlike reading novels and comics. Paradoxically and yet generally, some filmmakers have taken advantage of this particular and restrictive system to cause a particular effect on the spectators.

Alfred Hitchcock is one of the film directors who successfully use this particular restrictive narrative system in order to successfully manipulate the spectators, re-defining the concept of linearity in the cinematic projection. And Psycho, one of Alfred Hitchcockfs representative films, represents the power of linear narrative and the possible manipulation of the spectator. And it is this subtle manipulation that Alfred Hitchcock uses in the construction of Psycho, and its filmic narrative that shocks and unsettles the majority of spectators. This essay will therefore discuss this exceptionally experimental Hollywood film, and especially the relation of the filmic narrative and the filmic texture.

Psycho, a modern horror film, was produced by Paramount with Universal Pictures managing its production. Universal has been regarded a distinguished horror genre production company ever since the early 1930s. Psycho was released in 1960. When Psycho was screened in the movie theater, the ideal spectators must have been confronted upon viewing the film with unprecedented feelings of shock and/or anxiety. But how were the spectators able to overcome these overwhelming cinematic emotions presented through the particular narrative structure? And hence what were the intrinsic cinematic mechanisms that caused such an effect in the spectators and why to such a degree of intensity? | |

| | |

| R@Murder and Empathy

Psycho bewilders and stupefies the spectator by the unexpected sudden murder of the heroine, which happens after forty-six minutes have been screened. It is an act completely unexpected by the spectator, and therefore its sudden unanticipated reality mystifies and frustrates the spectator. The heroine is stabbed to death by an unidentified person, and the film provides neither reason nor additional information of the abrupt murder. This sudden act of removing the heroine from the narrative puzzles and petrifies the film spectator for two reasons.

Firstly, the heroinefs death signifies, to the ideal spectators, their own death. When she is stabbed to death in a motel shower room, they go through not only with the projected moment of the murder scene but also experience identical causative psychological feelings as the heroine does.

The ideal spectators have the inherent capacity to identify themselves with the heroine and therefore to imagine themselves in the position of the protagonists. They share, equal and hence personify themselves with the feelings of the protagonists as well as with those feelings that are caused by the filmic manipulation of the linear narrative. The spectator feels personal empathy and hence relate to the protagonist. And this in-personifying experience, out of the individual body in the reality of not-onefs-own conscious self, often inspires potential spectators to watch new films. It also challenges them to scrutinize the diverse points of views that the classical Hollywood film will offer and to incorporate these new experiences into their own. This is somehow self-substantiated by the more-or-less conscious effort on the part of the spectator who indulges in an excessive empathy. This empathic tendency of the spectator is carried to such an extent that they often avoid a retrospective self-analysis. This will be analyzed in Section Seven in detail ? the cinematic technique and the elaborate technical preparations for inspiring, prompting and manipulating spectatorsf empathy.

This section will discuss the significance of the protagonist in classical narrative films. The protagonists lure the ideal spectators into the diegetic world. Hence, the spectators as if being taken out away from their everyday reality and are absorbed in the fictional world on the screen, hence finding themselves experiencing the moral and psychological ordeals of the protagonists. In the case of Psycho, a well-known attractive actress, Janet Leigh, plays the main role. She is the person with whom most of the spectators more or less identify. At the time, Janet Leigh was a famous actress with a fifteen-year distinguished career in Hollywood . No ideal spectator would have expected the abrupt removal of the main heroine before even half of the film was over. Another cinematic convention has the spectator expect the impossibility of the heroinefs murder; the removal of the main character would leave the filmic narrative unfulfilled. Psycho, however, does not conform to the cinematic convention of the classical Hollywood cinema, and therefore the ideal spectators were logically puzzled and shocked at this unexpected narrative twist of the heroinefs murder.

The protagonists cinematically fulfill the roles of safety vehicles guiding the spectators through the complex labyrinth of narrative. The protagonists also function as a sort of estand-inf; the spectator visually experiences whatever the protagonists project in the diegetic world. And therefore they possibly cannot be, must not be, removed from the narrative since they act as the primary agent for the spectator. Nonetheless, Psycho breaches this established convention for the first time in the classical Hollywood film history. The moment the heroine is murdered in a motel shower room, the ideal spectators are deprived of the cinematic agent with whom they identify and are left to their own interpretative cinematic devices. The spectators are perplexed and confused as the death of the heroine indirectly means the death of the spectators themselves. Surely, this is the main reason why the ideal spectators are shocked and bewildered, and this narrative incompleteness of the filmic text may be the reason why Psycho still remains to be one of the most frightening films. Nevertheless, the first reason has little to do with the filmic texture. This section has only discussed the film in terms of cinematic conventions, and its approach is still limited to the external level only. The following section will accentuate the textual analysis of Psycho in order to find out the second reason for the spectatorfs confusion and their state of utter shock. | |

| |  |

| S@The Knife and the Windshield Wiper

In the previous section, I mentioned that the protagonist is suddenly stabbed to death without any prior narrative indication. This is exactly the central issue for the discussion of the cinematic obscurity, in which the filmic narrative conceals up to the shower scene its cinematic intention. This leads to the investigation whether indeed there has NOT been any cinematic indication of the narrative effect.

In order to illuminate this issue of narrative effect and the cinematic obscurity, it would be most helpful to look at another scene which precedes the murder scene; a scene where the heroine decides to steal the money at the sight of wads of bank notes. It is necessary to pose at this shot. Within the shot, there is a large photograph clearly visible behind her desk conspicuous for its unusual scenery [Shot A]. It is a plain photograph of a desolate desert without a single person, presenting nothing but a forlorn moribund atmosphere. The photograph hardly suits the office and this is probably why the spectatorfs attention would be inevitably drawn to it, although since it is a real estate office, a photograph of a landscape, whatever it is, would not be completely unsuitable to the atmosphere of the place. This photograph foretells the narrative, as the spectator later realizes that it has augured her destination. The heroine leaves the office only after half of a day (four minutes later on the screen), she then finds herself stopping overnight in a familiar landscape [shot B]. There is nothing alive but the weeds swaying in the wind around her car as a death-like silence falls on the scene, quite resembling the atmosphere of the photograph [shot A].

As I have mentioned in Section 2, the narrative form of a film depends on cinematic linearity. Any film is composed of shots and scenes, which are structured in a linear progression through which a narrative can be communicated and conceptually established. And it is this resemblance that indicates the narrative inference of Shot B being foretold by Shot A.

I refer to this foreshadowing because even the murder scene, the obscure narrative focal point of the film, is suggested through some previous images. The heroine, who is on the run from the police, comes to regret what she has done, and decides to return the money back to the office. After her conscious decision being made and cinematically explicated, she takes a shower. The shower, therefore, infers a cleansing of her guilt as several critics have claimed. All of a sudden, the shower curtain is drawn wide and an unidentified person slashes her naked body relentlessly. The stabbing act fragments not only her body but also the film itself and its narrative structure. In shot C, the killer casts his shadow on the translucent curtain, and in shot D, he leaves the crime scene. The forty-second murder scene between shot C and shot D is broken down into thirty-three shots. In the series of fragmentary shots, her scream at the fatal wound carries perceptual resonance, as if the film itself were being ripped up.

The murder delivers a considerable shock to the ideal spectators since they never expect the removal of the main cinematic agent with whom they have identified. It is necessary again to revisit our initial cinematic dilemma whether there is really no narrative indication, a warning, of the narrative twist. In fact, a close analysis indicates that there have been numerous analogous indicative images that infer the possible outcomes of the narrative.

For example, in the scene where the heroine is driving a car before she reaches the motel, we see the windshield wiper slashing through the heavy rain. The sequence implicitly envisages the murder scene through three analogous aspects of mise-en-scene. These are the splash of water, a close-up of the heroinefs distorted face, and the plunging trajectory of blade. The heavy rain precedes the hot water showering on the heroine; the movement of the windshield wiper precedes the plunging trajectory of the knife with the murdererfs elbow as a fixed point. These two scenes strikingly resemble each other. The murder scene has a great deal of effect on the ideal spectators. At the sight of brutality, they experience mixed and strange feelings. It is a frighteningly new yet simultaneously familiar scene. It is, indeed, an odd experience of deja-vu, experiencing the familiar as well as the unfamiliar. The spectator and the heroine undergo the moment of death twice. This is because the narrative and the filmic texture Psycho offers a repetition of ominous thread.

Psycho is an obscure and perplexing film of cinematic narrative and composition of images. Hence, because of its cinematic perplexity, the ideal spectators can never really anticipate the heroinefs death. For them it is totally unexpected. In Psycho the spectators are edged through a subtle manipulation to wander between the very opposite interpretations and therefore their interpretative grasp on the narrative plot is consequently precarious. This is the second reason why the ideal spectators are truly terrified at the shower scene. The murder offers two simultaneous readings; that is, a horrible surprise and a prophesied ordeal. Hereafter, I will call the two scenes we have discussed ethe scene of the knifef and ethe scene of the windshield wiper.f

The spectators of the time, of course, were kind of informed of the murder scene in the trailer (which was called eBates Motel Tourf). The trailer had been shown in movie theaters throughout the U.S. before the film was released in 1960. Consequently, the majority of the spectators must have surmised that something awful would happen as soon as the heroine began to take a shower. Her dreadful ending, after all, was forewarned both inside and outside the filmic text.

| |

| |  |

| T@The Ghoulish Murderer and the Dead Mother

As exemplified by the scenes of the knife and the windshield wiper, Psycho distinguishes itself by very subtle and obscure repetitions that give the ideal spectators a bizarre sense of deja-vu. This section will analyze how these repetitions and the sense of deja-vu are systematized in the film.

However, only under the condition that cinematic linearity is perfect a feeling of deja-vu is constructed. The preceding shots and scenes are sequenced to predict the later ones, as illustrated by Shots A and B. Shot A, however, only foreshadows Shot B and scarcely has such an effect on the spectators as it is the case with the scenes of the knife and the windshield wiper. In the latter scenes, the preceding shots are organized not only to predict the following ones but also to evoke the ideal spectatorsf of deja-vu, the result of which makes the film literally psychotic.

It has been mentioned before that the spectators is always subjected to a continual repetition of ominous threads in Psycho. Any narrative film, though, is constituted by repetition. Hence, the repetitive projection of the almost same image is often done within the film. Indeed, it can be argued that no narrative can be formed without repetition. In the case of Psycho, however, these cinematic repetitions are very subtle and deliberate, as typified by the esimulated subliminal effectf in the penultimate monologue sequence.

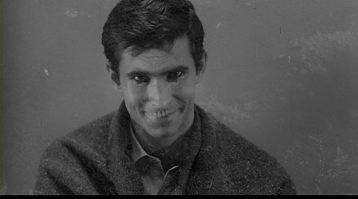

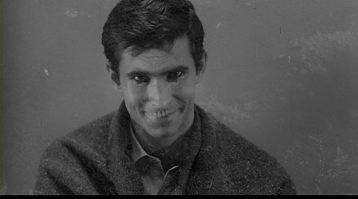

Of all the subtle techniques in the film, it can be argued that the most experimental is a close-up of Norman Bates overlapped with a dead head at the end of his/her monologue (Shot E). The ideal spectators should be too stunned and stupefied to be convinced and made to believe the cinematic authenticity of the projected image. It is natural that they react so, since what is directed toward the camera is the enigmatic grin of a ghoulish murderer/a dead head. It looks as if Norman were laughing with his lips rolled back from his teeth.

Shot E Shot E

However, it would be more appropriate to call this shot a esimulated subliminal effectf on the assumption that the majority of spectators do not notice the montage. This montage, the superimposition of images, is barely noticeable at the first viewing. The annually questionnaires that is conducted at the university confirms this imperceptibility. Most of the students who have taken a part did not notice this cinematic effect. Quite a few of them, though, did perceive a slight change in the scene. They were unable to say however what the image was and what it projected, and neither were I when I first saw the film. Feeling confused, I had to rewind the videotape in order to find out what the unusual and excessive image imposed on Norman really was.

It is hard to argue how effective subliminal images are, but at least it can be said that they have the following function. Subliminal images are usually inadequate in a narrative context. They are artificially inserted into the film, and this insertion is made indeed imperceptible to the normal perception of the ideal spectator. The spectators therefore accepts these subliminal images at a level of the mind below consciousness: at what we call the subliminal level. I should explain the effect in more definite terms.

Lately, I had an opportunity to talk with Ichiro Yamamoto about subliminal effects. Yamamoto was in charge of such cinematic effects while editing a different version of Rampo (1994, dir: Rintaro Mayuzumi, p: Kazuyoshi Okuyama), a Shochiku film that portrays the life of Edogawa Rampo. Okuyama, an executive Shochiku producer, re-edited the original film and thought of making use of subliminal images and their respective cinematic effects.

According to Yamamoto, subliminal images were projected onto the film at the speed of one frame per second. One frame is a single image on the strip of the film and measures a twenty-fourth of a second. One might question if one frame is visible to the eyes of the spectators. And if it is visible, we cannot call the image subliminal. Yamamoto, after several experimental showings among the staff, concluded that perceptibility depends on the degree of provided information. The images are only visible for those who are informed where they are ghiddenh. Others find it impossible to perceive them. It can be argued, therefore, that subliminal images take effect when the spectators fail to perceive what they could otherwise see in real circumstances.

In the forty to fifty frames (approximately two seconds) during which a close-up of a skull (provably the mummied motherfs head) is overlapped on Norman , the ideal spectators experience the eerie visual effect in a different way from subliminal effects. In the scene, they see what they could not see in certain circumstances, and this is what I have named the gsimulated subliminal effect.h The ideal spectators are consequently taken by surprise when they found themselves staring at the image of Norman/dead motherfs grin. Psycho, indeed, is the film that compiles these simulated subliminal effects, as exemplified by Shots A and B, and the scenes of the knife and the windshield wiper. The ideal spectators, in their visual memories, have Shot A overlapped on Shot B, the scene of the windshield wiper on that of the knife, as well as the dead mothers skull on a close-up of Normanf face.

Yet, this does not fully explain the significance of the penultimate monologue sequence. In the superimposition, the ideal spectators undergo a peculiar sense of deja-vu as well as of deja-entendu: the scene is deliberately premeditated to cause the double effect. The following section, therefore, will discuss the relationships between the repetitions and the senses of deja-entendu and deja-vu. The issue will eventually be discussed in relation to empathy, which should underline the essence of horror that Psycho presents and projects.

| |

| | |

| 6@A Sense of Deja-vu and Deja-entendu

Just before the monologue scene, a psychoanalyst gives Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) diagnosis. Norman is diagnosed with having two personalities, Norman as his very self and Norman his mother. Norman is unaware that he has been acting two roles; namely, the pathologically jealous mother who killed the women Norman was attracted to, and the pathetic son who covered up all the traces of the crimes he believes his mother committed. However, after the fact that his mother had been dead was revealed, the dominant personality of Norman has become his mother. Because he has now completely assumed the role of his mother, he/she insists on his/her innocence in jail: gHe [Norman] was always bad and in the end he intended to tell them I killed those girls.h What Norman says is completely true, as far as the real murderer is Norman, not his dead mother. At the same time, through becoming his mother, Norman successfully escapes the blame for what he did. He obviously succeeded in escaping from reality firstly by acting out two personalities and then by becoming somebody else.

However, the central issue in the scene for the ideal spectators is how the shift of characters, from Norman to his mother, is presented on the screen. Interestingly enough, this shift is made by sound effects: by means of voice-over narration and off-screen voice, both of which are simple sound techniques. Off-screen voice is the one whose source is in the space of the scene but in an area outside the frame; voice-over narration is the charactersf inner monologue directed towards the spectators.

The scene begins with an off-screen voice. After the psychoanalystfs diagnosis is related, a policeman brings a blanket for Norman, who feels chilly in the room, which is under surveillance. His motherfs voice is heard saying, eThank you.f Norman/Mother is placed to the left outside the frame. There follows an editing cut into the room where Norman , wrapped in the blanket, is sitting in a chair against a blank wall, and his motherfs voice is heard again. This is the moment when the ideal spectators are tricked into believing that Norman/Mother is speaking. It is natural that they believe so, because he/she thanked the policeman in an audible voice. As the camera begins to track in towards Norman , the spectators cannot help but to notice that something is different. Norman/Mother does not speak but the spectators can hear his inner thoughts through voice-over. And because this change is barely perceptible, the spectator misses the shift in sound techniques, a change from off-screen voice to voice-over. Motherfs voice-over continues. She blames Norman and insists on her innocence: gI could not do anything except just sit and stare, like one of his stuffed birds.h

At the moment that Norman/Motherfs self-justifying monologue is over, the ideal spectators go through a peculiar sense of deja-vu and deja-entendu at the sight of the superimposition in Shot E (the simulated subliminal effect explained above). The scene intends to remind the spectator of two preceding shots and one preceding sound effect.

As for the two preceding shots, the dead mother first refers more to the mummyfs face than to an abstract symbol of death. The ideal spectators naturally, through their visual memory, have Norman overlapped with the mummy sitting in the chair, an impression intensified by the murdererfs insistence on his/her innocence, being ga harmless person who just sat and stared.h Secondly, the bust shot of Norman/Mother reminds them of the heroine at the wheel on the run. The camera was also in a close-up position as she was sitting at the wheel behind the windshield while wipers slashing across the heavy rain. The ideal spectators should likewise recognize the analogous sound effects here. Namely, the heroinefs inner thoughts were delivered through voice-overs, as were Norman fs in the monologue scene. These two scenes strikingly resemble each other not only at the level of visual and sound effects but also in their high standard of quality. The scenes share in common the rare structure of a projected subject being accused by way of a voice-over: a close-up of Norman is enveloped by his motherfs strong words and that of the heroine, and by those of her boss and others. This should explain what I have called a peculiar sense of deja-entendu in this filmic text.

The ideal spectatorsf visual and auditory memories are inextricably intertwined. A close-up of Norman overlapped with a dead head dissolves to the heroinefs car being dragged out of the swamp, which implies that the victimfs bones are still inside the car. As soon as the title gThe Endh is overlapped over the shot of the car, morbid music wells up and the graphic pattern of the opening titles is reprised. The graphic pattern of torn and split images is therefore displayed twice in the film; namely, at the opening and at the ending. The graphic images predict and reiterate the scenes of the knife and the windshield wiper. Throughout the film, we actually see a repetition of the ominous threads of the murder scene in which the heroine is slashed and the film itself seemingly ripped up. (The actress Janet Leigh has her name split in two graphically in the opening credits.) In Psycho, these systematic repetitions and differentiations form a canonic text that confusingly echoes in the ideal spectatorsf memories. | |

| | |

| 7 The Spectatorsf Auditory Sense

Now that we have explicated the systematic relationships between the repetitions and the sense of deja-vu and deja-entendu, this last section will discuss the issue of empathy. We have analyzed how the ideal spectators experience a peculiar sense of deja-entendu: the voice-over in the penultimate monologue scene, for instance, was foreshadowed by that in the heroinefs flight. The deja-entendu further takes effect when Psycho methodically prompts the ideal spectatorsf empathy. Understanding this concept of cinematic empathy, it will help us to conceptually comprehend the essence of Hitchicockfs modern horror.

As I mentioned in Section 3, the ideal spectators always take an excessive delight in feeling empathy. They see, hear, and think about whatever the characters experience in the diegetic world, and they wish to incorporate the charactersf motions and emotions into their own.

For example, in a close-up of the heroine on the run, several voices are heard: gShe was flirting with me and took all that moneyh (the voice of the rich customer); gI told you, you shouldnft have had it all in cash.h (the voice of the real estate boss). While these words are scripted by her imagination, the voice-over makes them echo convincingly so that the ideal spectators accept them as if they were themselves on the run, undergoing an identical fear of accusation and guilt.

At that moment, the ideal spectators, in fact, have already identified with the heroine due to the effective technique of point of view shots. The spectator first comes across a point-of-view shot when the heroine packs the $40,000 she stole from the office. The money is repeatedly shot from her point of view, which gradually prompts the ideal spectators to mistake her viewpoints for their own. Consequently, they identify with the heroine. This is the moment when they inevitably get themselves involved in the diegetic world of the classical Hollywood cinema. There is no real need to discuss the issue of the spectatorfs identification with the look of the camera and then with the look of the characters, since this has been discussed by several film scholars and film critics, such as Christian Metz and Stephen Heath. The close-ups and voice-over narrations by protagonists are the basic methods by which the classical Hollywood cinema prompts the spectatorsf empathy. By means of these two techniques, the ideal spectators recognize what they wish to see and hear. It is also significant that the neon sign gBates Motel Vacancyh becomes visible in the heavy rain from the heroinefs point of view when the motion of her car terminates. Twenty minutes after that, the heroine herself is forced to end her motion. She does become vacant.

The scene with the windshield wiper then leads to the penultimate monologue scene via the scene with the knife. There is more to discuss, such as the cinematic trick of shifting from the off-screen voice to the voice-over in the Norman fs monologue. The trick proves to be successful when the ideal spectators mistake the murdererfs inner monologue uttered by his mother for a real one.

Until that scene, the ideal spectators had not allowed to identify themselves with Norman, the enigmatic motel owner. Before half of the film was over, they were deprived of their object of identification (the heroine/Janet Leigh) and had difficulty in finding out what to do for the rest of the film. They had a certain reserve towards Norman and kind of refused to take him for their stand-in. Instead, other minor characters involved with the heroine (the private detective who investigated the case, and her sister after he was murdered) somehow functioned as her possible substitute. But now, the only remaining character on the screen is Norman .

Just before the scene, the ideal spectators first hear Norman speaking in his motherfs voice outside the frame and take it for an off-screen voice. The voice continues in the following, so they naturally believe that Norman is talking to the policeman, who is supposed to be outside the frame. They soon realize, however, that it was the murdererfs inner monologue. This leaves them at a loss. The scene catches the ideal spectators unprepared. This same identical situation occurred at the murder scene. The murder in a shower room delivers a considerable shock to the ideal spectators because of their identification with the heroine. Their identification was reinforced by such traditional techniques, as the use of close-ups, point-of-view shots and voice-over narrations. In the monologue scene, they are then unconsciously trapped into identifying with Norman, the killer, an impossible object of identification, for all their cautious observations of his personality up until that moment. The ideal spectatorsf auditory senses are so naive that such a minimal trick, such as the shift from the off-screen voice to the voice-over narration succeeds in deceiving them into feeling the most impossible and gruesome empathy.

This is a moment in which the ideal spectators suffer a kind of bizarre frustration because Norman reminds them of their own individual traits. The spectators almost always takes a ghoulish delight in experiencing empathy: they constantly wish to be someone else in a movie theater and in doing so avoid self-analysis. The murderer with whom they momentarily identify also wishes to be someone else, namely his dead mother. And he succeeds in identifying himself with his mother to such a degree that he totally loses his own identity. At the sight of Norman fs gruesome face [Shot E], who can deny that he or she might be the logical consequence of the identification of the film spectators?

Note

This essay is a slightly different English version of a chapter in my book entitled Eiga to wa Nanika? (What Is the Cinema?) published by Misuzu Shobo in 2001 in Tokyo . | |

| |  |

|

Shot E

Shot E